Holding back the floods in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh’s flood-prone Haor region, where flash floods threaten homes and livelihoods each monsoon, a project implemented by national financial institution Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) and supported by Germany’s International Climate Initiative (IKI) offers communities new tools and knowledge for adapting to the effects of climate change.

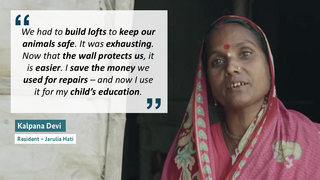

Almost 3,000 residents are experiencing increased security and stability in their everyday lives, thanks to over 1.5 kilometres of flood protection walls, tree buffer zones, and maintenance training. “Before, we lived in panic and anxiety,” says Kalpana Devi from Jarulia Village in Bangladesh’s Haor Region. “We had to build lofts to keep animals safe. We’d carry bamboo and tie up our cows when the floodwater came. It was exhausting, and still nothing ever felt secure.” The region is a unique wetland ecosystem in the northeast of the country, seasonal flooding is a part of life. Locally called Afal, flash floods have a significant effect on the region, one of the country's four vulnerable climate hotspot areas.

In recent years, climate change has intensified rainfall and erosion of the villages through the afal waves, leaving low-income communities with fewer options and increasingly vulnerable. As more than 70 per cent of houses are made of mud, they are affected by rain and storm waters that damage homes and other buildings. Each year, families like Kalpana’s spend the equivalent of hundreds of euros on flood repairs, relying on temporary solutions like sandbags and bamboo fencing. Each year, the water returns and puts pressure on the villages and villagers once again.

International backing for local purpose

Launched by the Government of Bangladesh in the late 1980s, the Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) is tasked with financing the country’s development projects as part of its vision to bring an end to poverty. Between 2023-2025, with support from the German government’s IKI Small Grants programme, PKSF ran a pilot project to test long-term, climate-resilient infrastructure in some of the region’s most flood-exposed “hatis” – small, isolated village-islands in the Sunamganj district in the country’s northeast. For PKSF, the project offered a chance to pilot new methods in a region often overlooked. “Our role at PKSF is to bring climate-smart development to places where traditional support doesn’t reach,” says AKM Nuruzzaman, General Manager for Environment and Climate Change at PKSF.

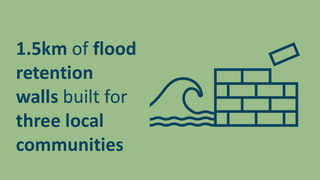

“The Haor region is difficult to access, but we believed in testing solutions here because the need is real – and so is the community’s resilience.” Partnering with the three local NGOs Thengamara Mahila Sabuj Sangha (TMSS), Friends In Village Development Bangladesh (FIVDB), and Padakhep Manobik Unnayan Kendra (Padakhep), the project involved constructing over 1.5 kilometres of wave-resistant flood retention walls, planting 1,300+ flood-tolerant indigenous trees, and elevating schoolyards and community grounds to serve as safe spaces during floods. “The living space is safe and protected, women like Kalpana can now build and expand their own home,” Nuruzzaman outlines.

Funding funders to disburse resources in the Haor region

Working with the IKI Small Grants “fund the funder” approach allowed PKSF to select organisations on the ground with deep ties to the local communities. Using this method, IKI Small Grants channels funding and technical support through intermediaries like PKSF in Bangladesh who then identify, finance, and support local organisations and community-based initiatives. Led by PKSF, the advantage of the selection process through the institution lies in the fact that it can engage local organisations for climate and biodiversity action in their own language and context – directly and effectively.

This model strengthens local ownership, builds long-term capacity for entities like PKSF, and ensures that climate and biodiversity solutions are suited to their context and can grow and be adopted elsewhere. It’s a strategy that lends partners more responsibility to disburse funds and resources themselves and empowers countries to take the lead in driving their own climate resilience and adaptation.

Challenging work leading to local ownership

From the outset, the work came with challenges. The three villages are very remote. “Just moving materials to the sites was a major hurdle,” Nuruzzaman recalls. “In dry season, there are no waterways. In rainy season, there’s no dry land to store construction supplies. Technical staff didn’t want to stay in such remote areas. We had to build temporary shelters and work with local labour wherever possible.” To make the impact last, PKSF built the project to ensure ownership could remain local. “If anything goes wrong in the future,” he adds, “the villages can maintain things by themselves – without asking experts from the outside.”

Community members contributed labour, received training on maintenance, and participated in climate adaptation workshops. Women especially noted improvements in freedom of movement after dark, when the rains used to inundate living spaces, and sanitation. Elevated grounds and protection walls make daily life more secure. Boats can now dock properly, transporting people and goods in the region.

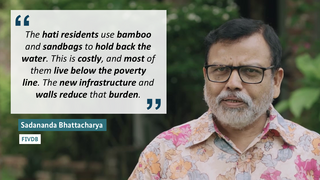

Engineer Sadananda Bhattacharya, who oversaw part of the project with local NGO FIVDB, observes: “These families are always in a state of panic when the monsoon season arrives. The residents used to spend 25,000 to 30,000 taka (between 170 and over 200 euros) every year just to hold back the water with bamboo and sandbags.”

Beyond infrastructure

Kalpana sees the benefits in everyday moments. “I no longer have to worry every time clouds gather. Now that the wall protects us, it is easier. I can save the money we used to spend on repairs – and now I use it for my child’s education. That’s the change.” The project now protects some 2,700 residents across three hatis, with interest from neighbouring communities growing.

PKSF is preparing larger-scale proposals based on lessons learned to expand these models to other vulnerable regions – from drought-prone areas to cyclone-exposed coastlines. “We are trying to scale up this project,” Nuruzzaman explains. “We are approaching different development partners, and we are also talking with the government so to replicate this kind of project.” For now, the Haor villages have something they didn’t before: a greater sense of safety, a new level of flood protection, and the tools to safeguard their villages themselves.

About IKI Small Grants

IKI Small Grants, implemented by the German federal enterprise Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), funds local actors which are the driving force for change and essential for effective climate and biodiversity action worldwide. The programme is part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI), which is jointly commissioned by the German Federal Government. IKI Small Grants fosters bottom-up solutions while strengthening capacities of local actors.

The link has been copied to the clipboard

Contact

IKI Office

Zukunft – Umwelt – Gesellschaft (ZUG) gGmbH

Stresemannstraße 69-71

10963 Berlin

More about the organisation

Funding priority

IKI Strategy

The IKI aims to achieve maximum impact for the protection of the climate and biodiversity. To this end, it concentrates its funding activities on prioritised fields of action within the four funding areas. Another key element is close cooperation with selected partner countries, in particular with the IKI's priority countries.